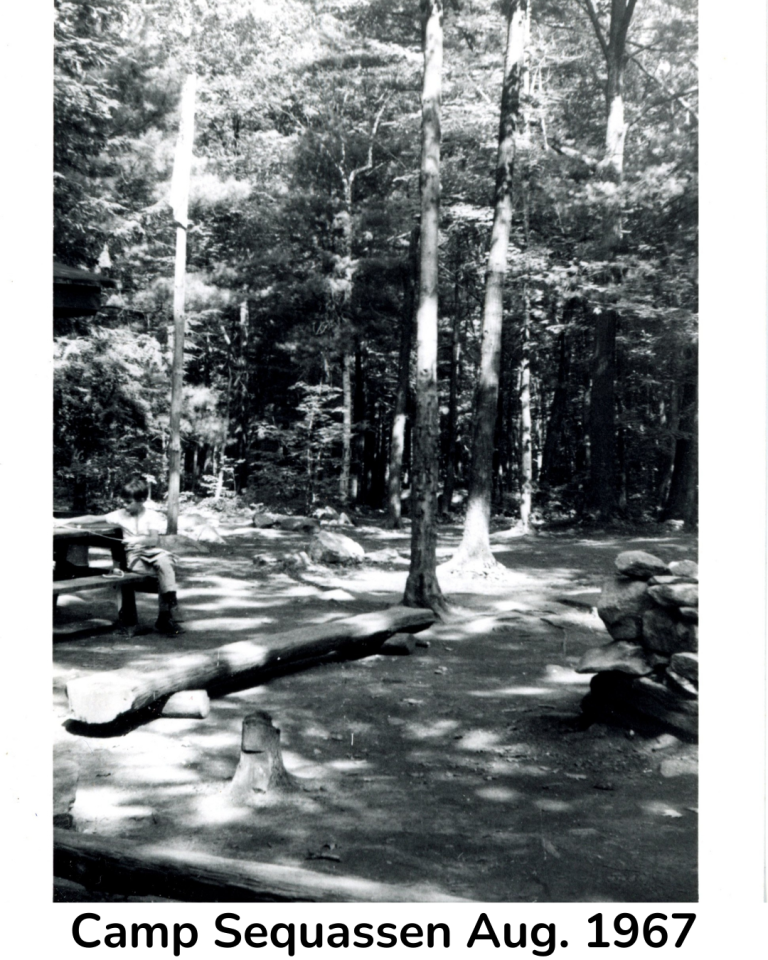

A New Site for Camp Sequassen

The most exciting local development of the year [1927] was the acquisition of a new site for Camp Sequassen, 125 acres of land on West Hill Lake in New Hartford, fifty miles away. *

Predictably, there were some who objected to the fifty miles, but this was no longer valid, for life itself had changed in America. Almost every family had a Ford Model-T, or equivalent, in which it traveled the dusty miles to camp and far away. Travel was for pleasure, and on summer weekends, the flivvers chugged along, filled with proud riders, as the live stock kicked up its heels and gave the right-of-way. Like the umbrella ants of the tropics, each family carried its tin leaf, or was carried by it, in endless processions to more and more distant destinations.

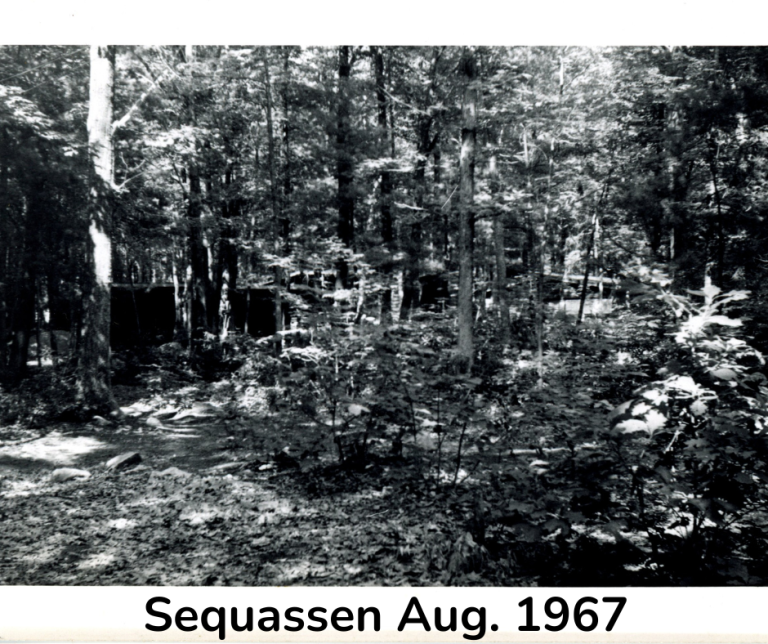

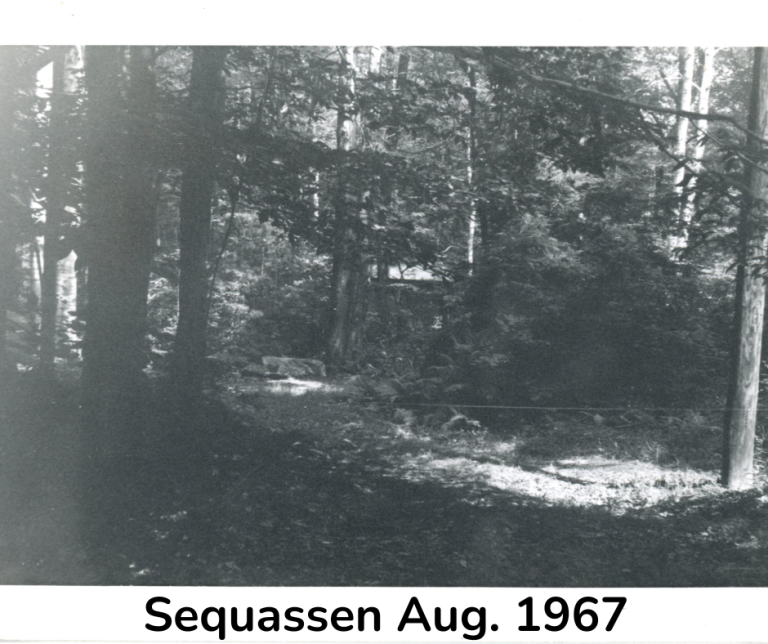

The new camp, at about a thousand feet above sea level, was at the trailing end of Vermont’s Green Mountains via the Berkshire Hills. The once spectacular ranges, sculptured by glaciers and softened by long weathering, had been in the making for half a billion years before we met them in the Pleistocene. Now the terrain was a gentle spill of hills, their soft contours ribbed with outcroppings of ancient rocks and sprinkled with quartz erratics from distant mountains, relics of an age of ice.

The erratics held the coolness of the summer nights and “sweated” on days of high humidity, making cool licking places for the small inhabitants of the forest. And, on cold nights, a young camper, sleeping out, might almost feel the edge of the glacier nudging him in the back.

The soil was rich, what there was of it. The ground was luxuriant with running pine and bushy mountain laurel, and held such wild secrets as the moccasin flower, spicy wintergreen, and rattlesnake plantain. (How pleasing that a botanist should name a plant to compliment a snake!) In the southwest acres we had swampy lands, lush and tangled with spicebush, witch hazel, sassafras, alder, wild orchids, and the popping jewel weed.

The early farmers had found the soil shallow and the going tough. Their old stone walls traverse the woodlands still, attesting both to their industry and to their defeat. The tall, unkempt giants of sugar maples had not been tapped for years, and the gnarled apple trees were rapidly being shaded out although still bearing some runted and knobby fruit for the chipmunks and the nocturnal deer. After the farmers, the red cedars, blueberries, and weedy gray birches had taken the land; then the deciduous woods, maple, beech, oak, white, black and yellow birch, hickory, and ash subduing the gray birches, and being themselves encroached upon by the hemlocks and the pines. Plantations of red and white pine had been started by the American Brass Company, a prior owner which had once had need for the wood. Now the pines are high, and a proud wind sounds through the tall green groves.

The discouraged first families, whose roots belonged in the soil, had gone westward with the fever of the forty-niners, or as later hopeful emigrants to the western lands. What they left behind was sheer beauty, wild land to wander in, rugged land in which to grow, and pretty land to love.

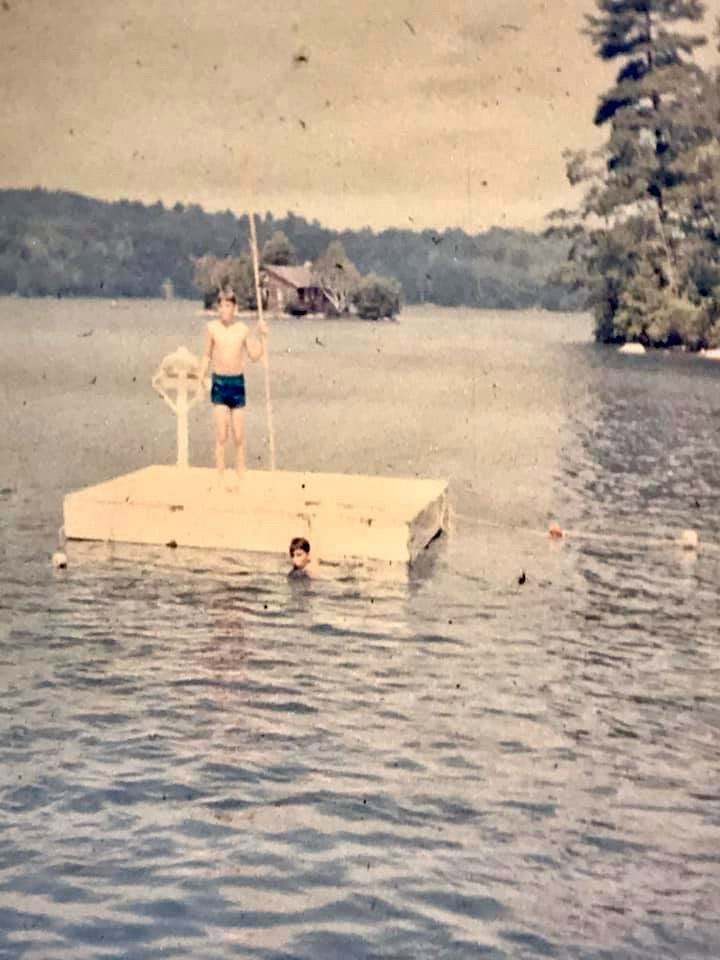

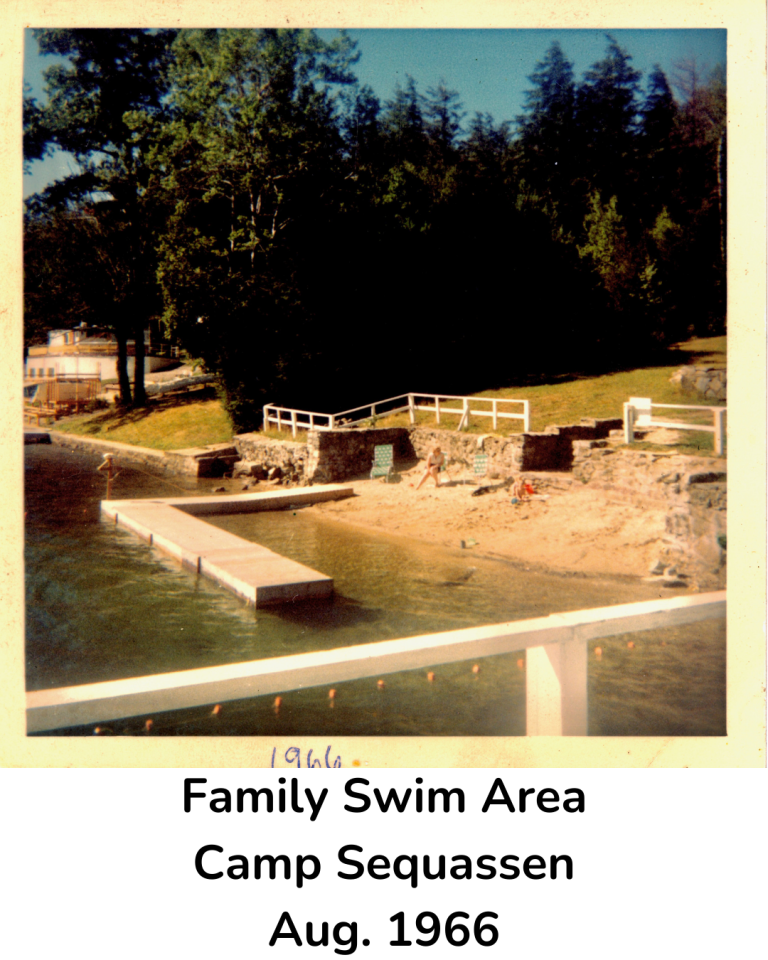

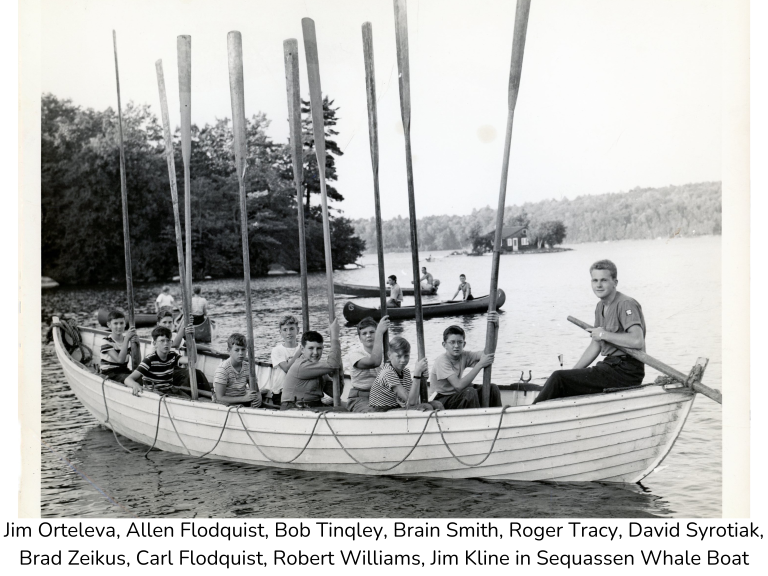

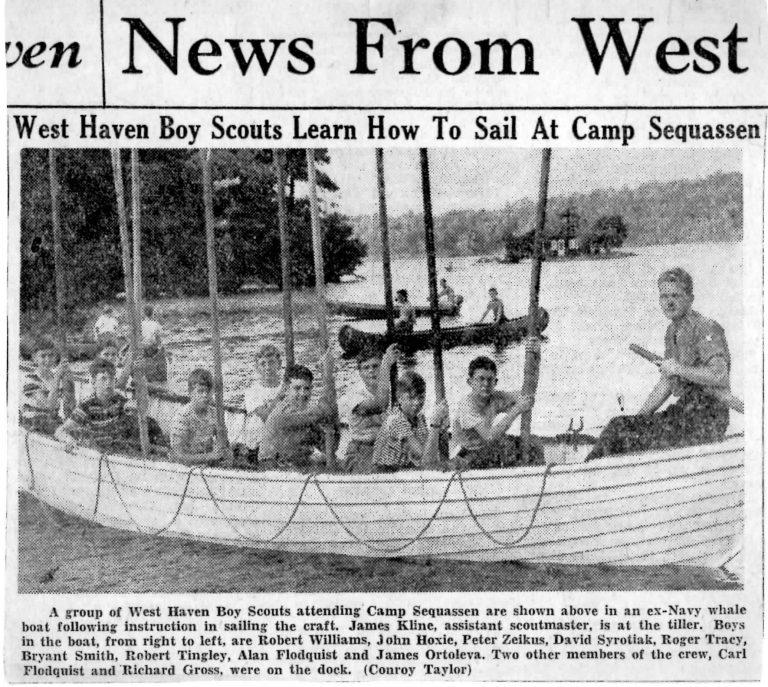

While our back acreage was adequate we had only a tiny, pie-shaped wedge of land on West Hill Lake, about the width of a wagon road at the vertex and as wide as a football field at the base. This was far too little, and it left us a problem to solve. The spring-fed lake had once been known as Shepherd’s Pond, and, before that, by the Indians, Wonksunkmonk. It was reputed to be the clearest lake in the state, and the Scouts could see a coin on the bottom at a depth of ten feet or more. They liked to explore its depths with open eyes, and one underwater swimmer sputteringly surfaced to report that he had stared a rainbow trout straight in the eyes and that “they” had waited to see which would blink first. And a winter group, skating on black ice, followed a school of bass for more than a hundred feet before the fish disappeared into deeper water. Long before they sensed how beautiful it was, the boys discovered how much fun the lake could be.

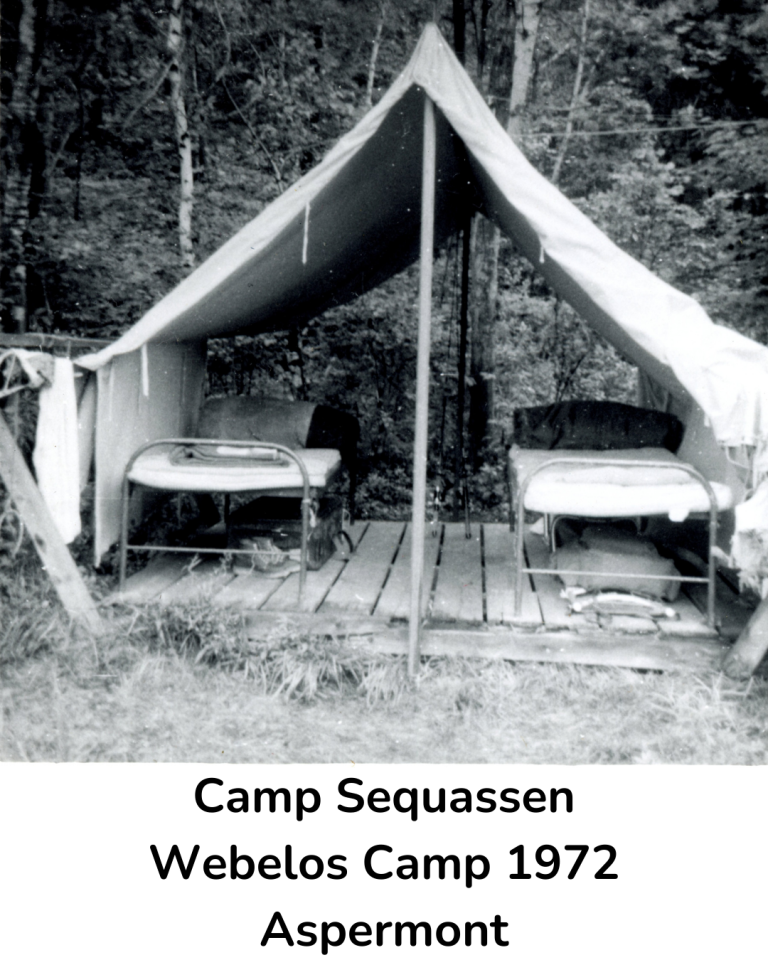

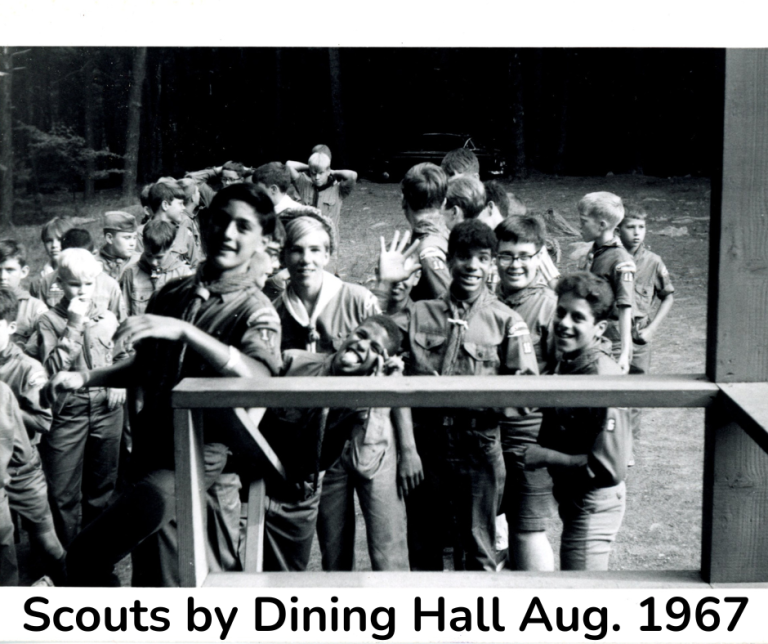

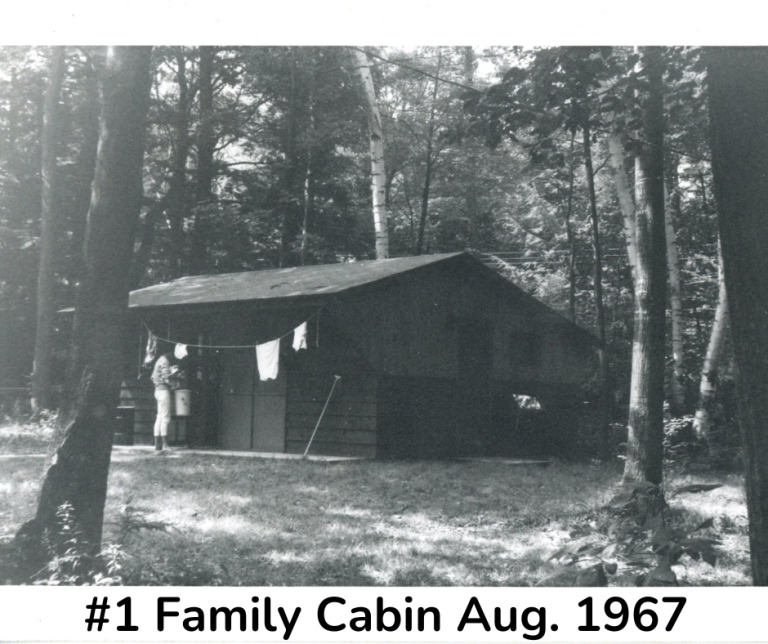

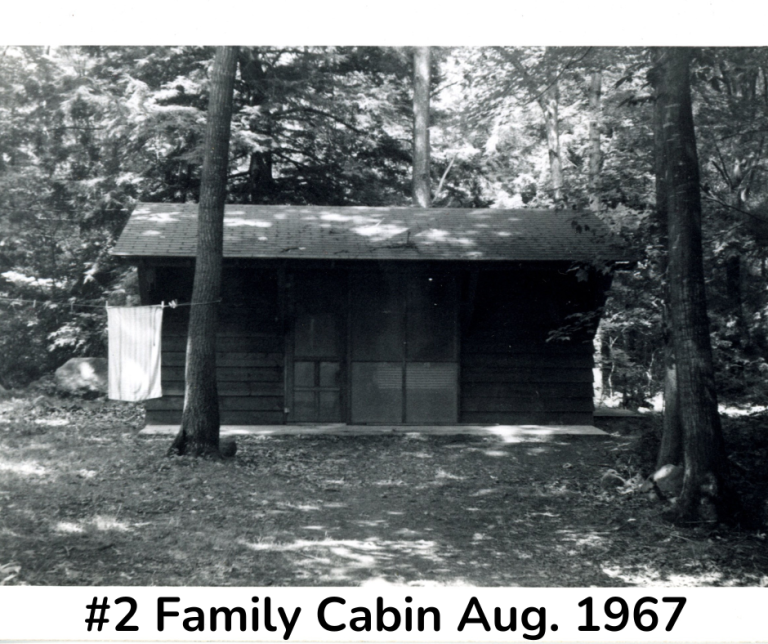

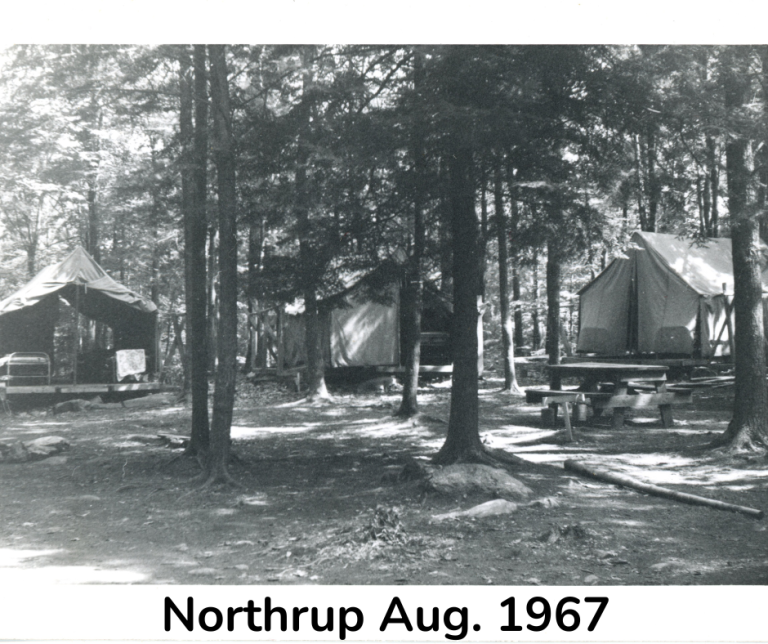

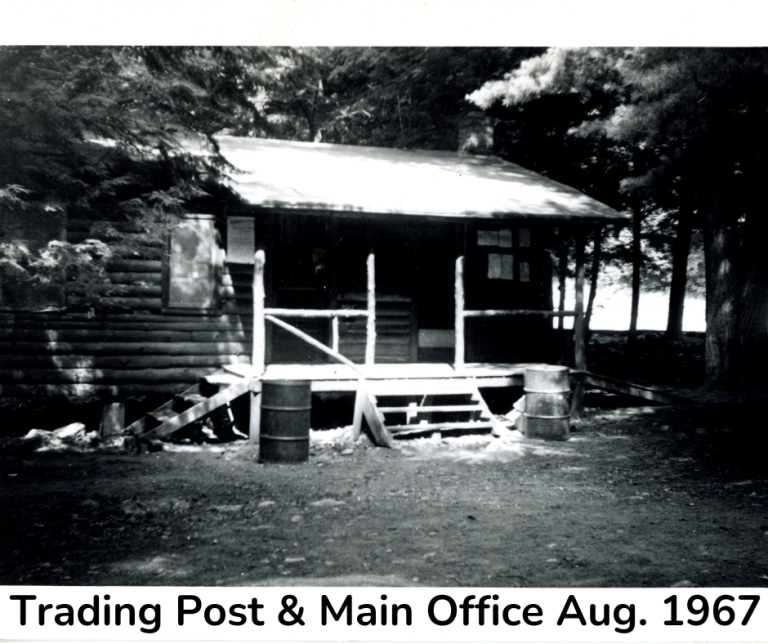

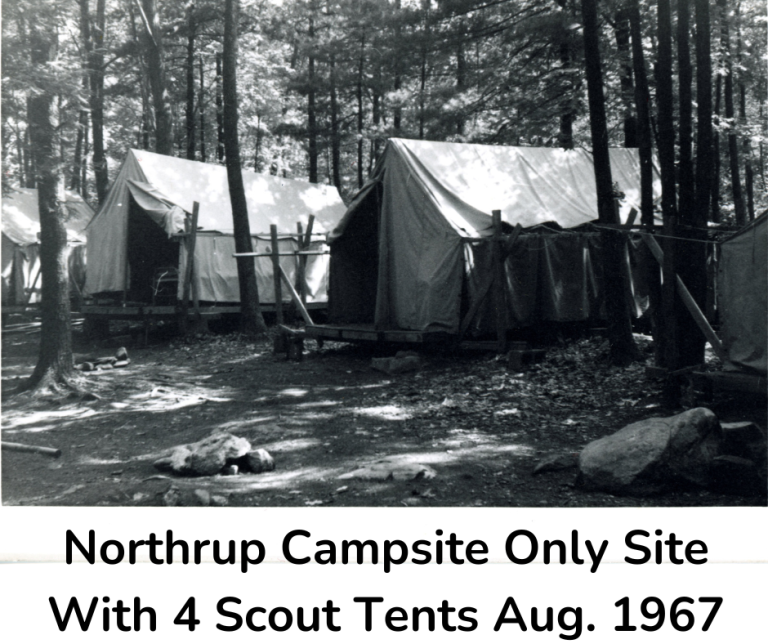

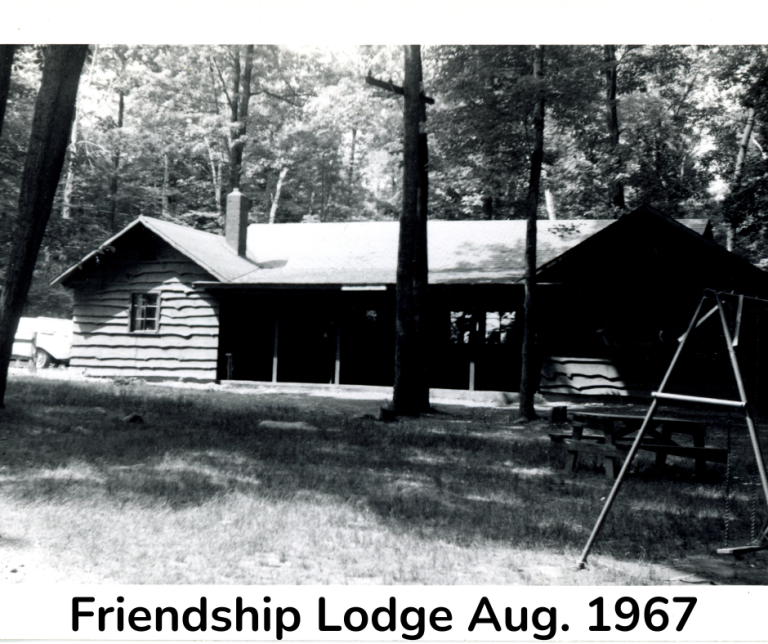

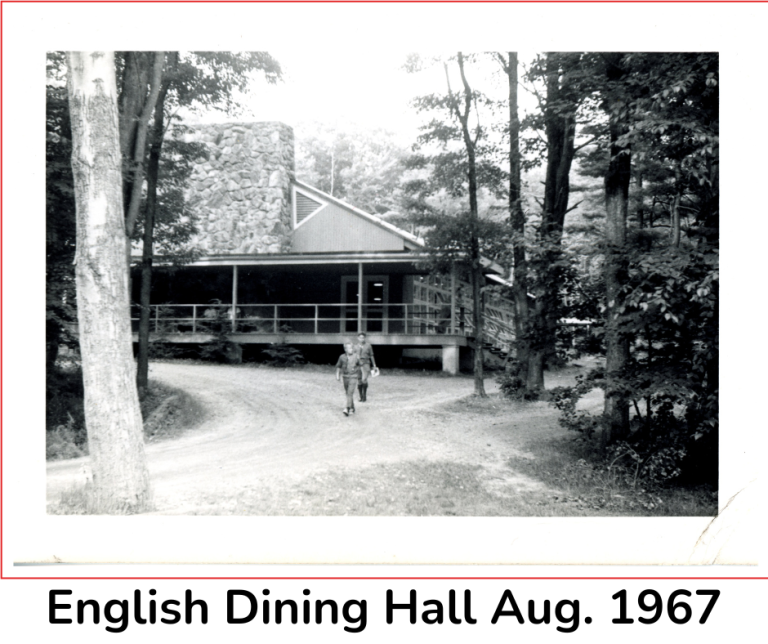

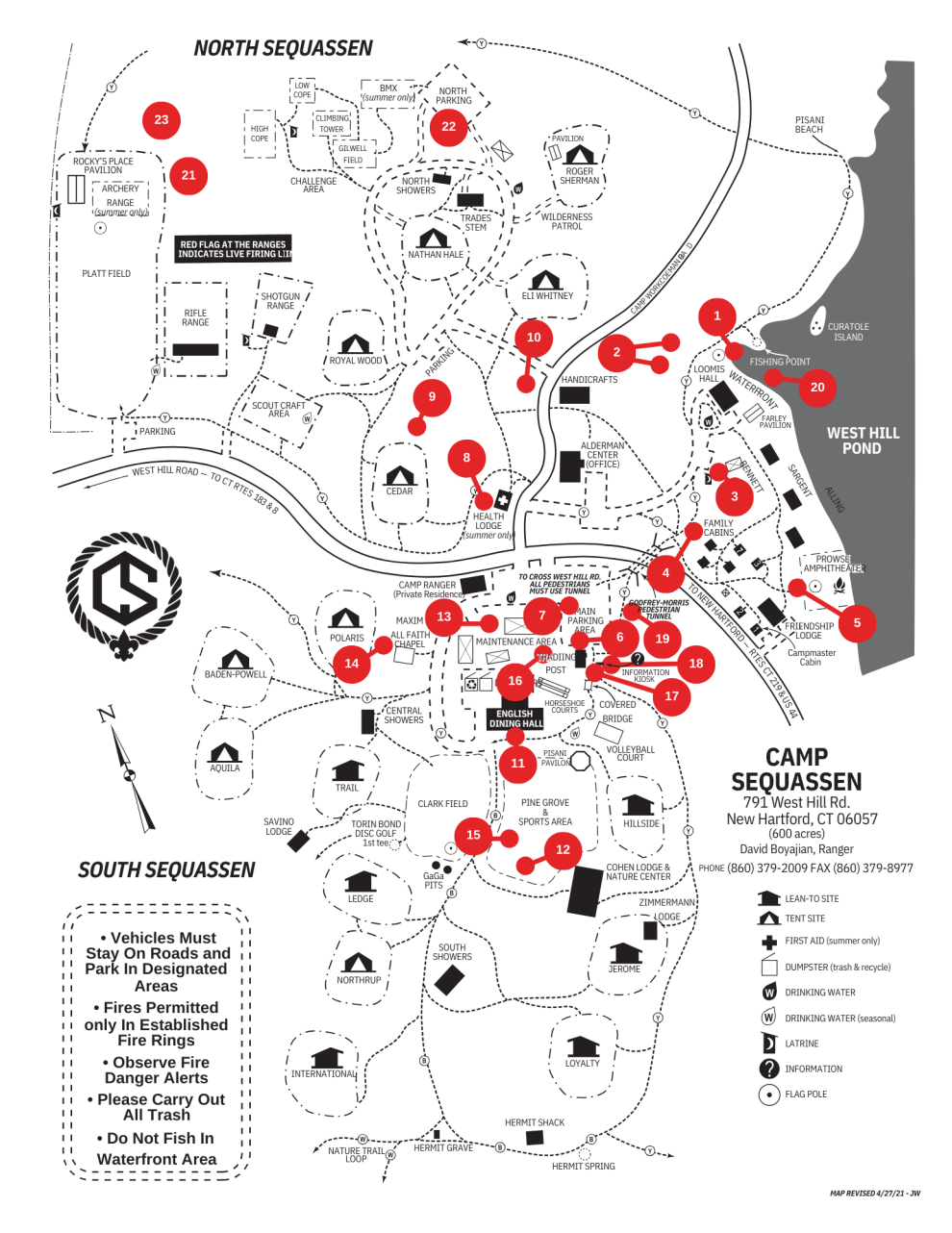

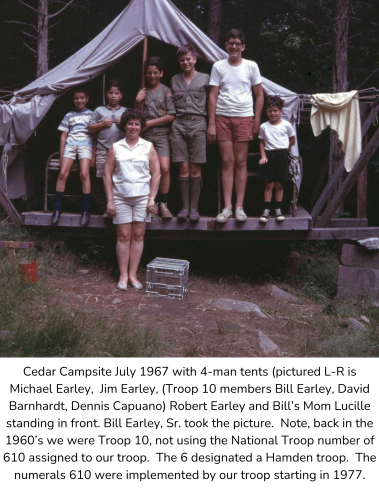

By summer a messhall, office, infirmary, and nature house had been built at camp. Drinking water came from the lake initially, but a deep well was later drilled and pumped with a gas engine. Electricity was still several years away. Seven original campsites were laid out. They were CEDAR, FARVIEW, PINE, MAPLE, HILLSIDE, LEDGE and TRAIL. Sanitary facilities were provided through three “country clubs,” so named, unofficially, because they had nine holes and a water hazard.

The Council had gone into debt for the camp, not knowing that a deep depression was on the way. Yet, it had made a good start on a great new camp, and the first season closed on a high note of optimism. The final banquet had become a tradition, and turkey, in those days, was turkey, usually from which the boys had helped to pull the feathers.

That winter the first of a long series of Christmas camps was held at the new Sequassen, and the Scouts learned at first hand that “He who cuts his own wood is warmed twice.” The local farmers were still using the pond to cut ice, and the camp shared in this annual harvest. An ice house was built on the waterfront in which the ice, stored deeply under sawdust, kept until summer. There were no newfangled contraptions such as electric refrigerators at camp, but the boys, in their spare time, were fashioning a miraculous new device, the crystal radio.

In 1928 the camp operated with a balance of $150. Council committee chairmen included H. S. Graves, George B. Lovell, W. W. Knight, Ira V. Hiscock, J. H. Clime, G. H. Gould, and T. R. Sucher. Meanwhile, the first Sea Scout patrol had been formed. It was the HECTOR of Troop 9, with Theodore F. Tuttle in charge.

* The “first” Camp Sequassen was located on a few acres on a small pond in Southington, in 1922.

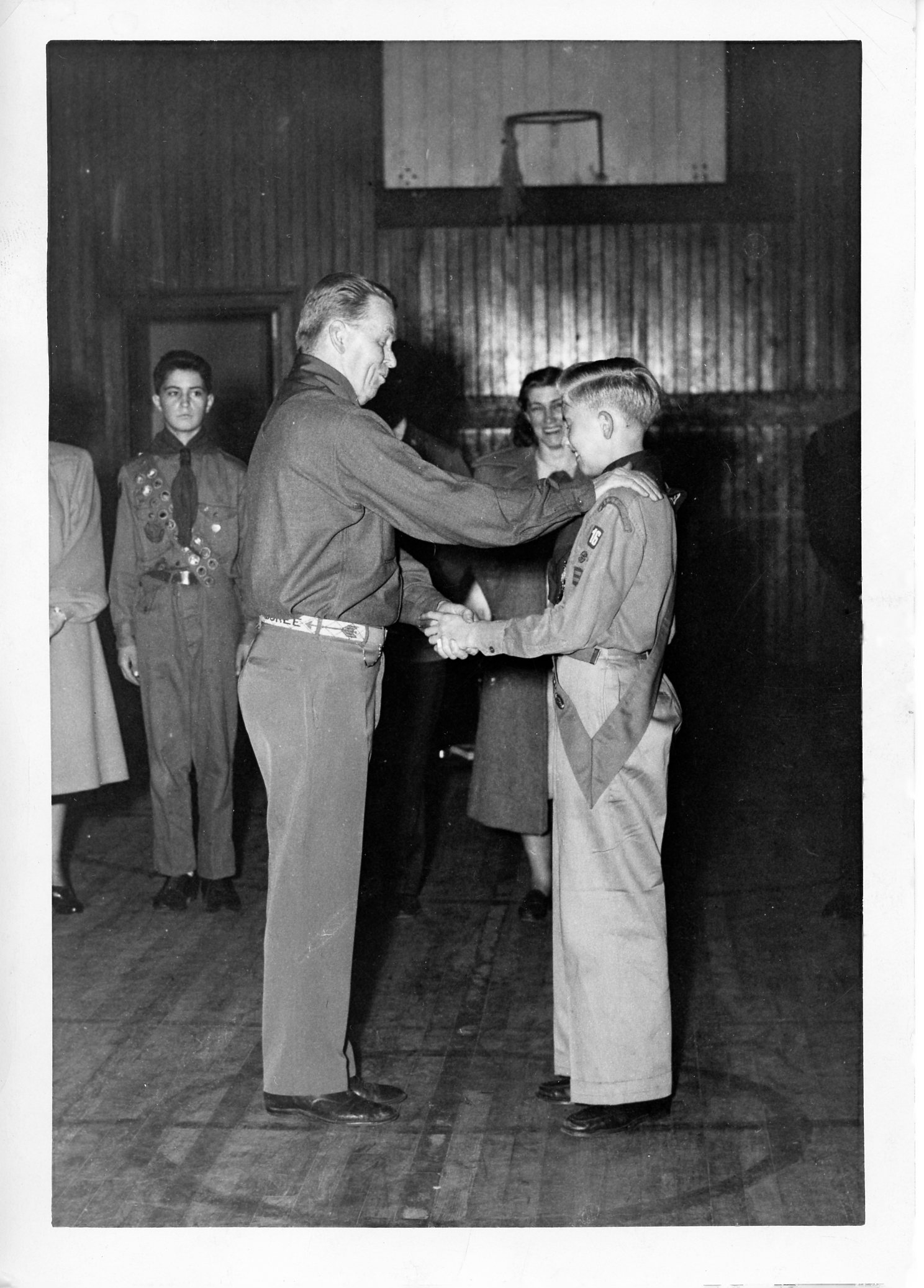

From: No Larger Fields – The History of a Boy Scout Council 1910-1963, by Samuel D. Bogan, pages 14-16.